In the most combative debate of the Denver mayor's race yet, candidates sharply criticized their rivals' positions on a host of issues, notably on public safety and homelessness, with Lisa Calderón and Andy Rougeot finding themselves in a testy exchange over policing.

Calderon said Rougeot doesn't know what he is talking about when it comes to policing.

Rougeot refused to back down.

Rougeot, the only Republican in the crowded field of mayoral aspirants, wants to add 400 police officers and "fight for Denver's future." Calderón insists more police officers do not lead to greater public safety, insisting the city should explore options to "avoid violent policing."

Denver is struggling to fill vacancies in its police ranks, which led current Mayor Michael Hancock to include enough money in his final adopted budget to hire more police officers.

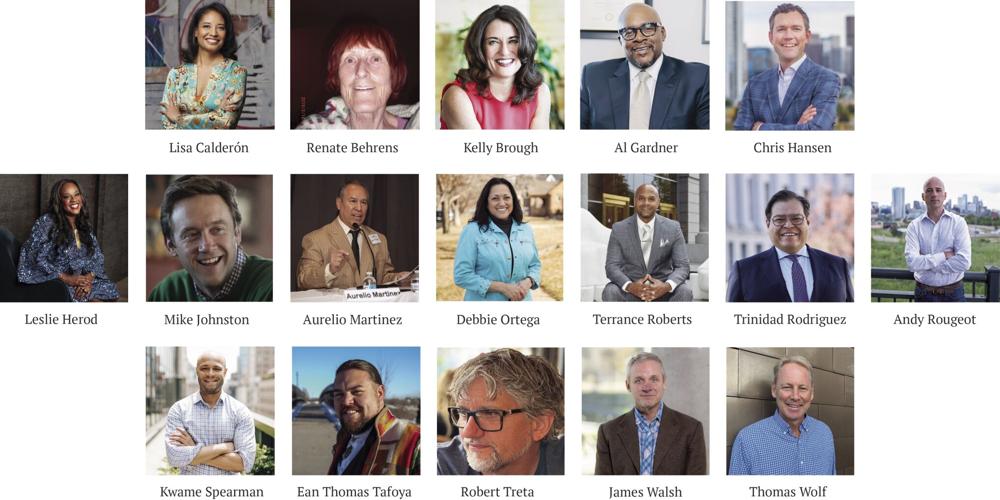

Eleven of the 17 candidates participated in Wednesday night's debate, where the candidates pressed each other on their positions on the city's most pressing challenges. A recent poll shows the race is completely up for grabs, with three candidates in a three-way tie. Mike Johnston, Lisa Calderòn and Kelly Brough each have the support of 5% of respondents, though this is just outside the poll’s margin of error.

Of those surveyed, 58% say they’re undecided.

The debate was testy.

Anusha Roy recaps some highlights from 9NEWS' second Denver mayoral debate.

Rougeot interrupted Calderón several times as she attempted to respond to his points, leading 9News moderators Kyle Clark, Anusha Roy and Marshall Zelinger to step in.

"Nobody can hear either of you when you talk over each other or when people clap," Clark said, quieting the crowd and the candidates.

Rougeot, in an attempt to defend his position, highlighted a 2009 Obama-era stimulus package that increased funding to police departments nationwide. He said this led to noticeable drops in violent and property crimes, hailing it as a "clear example of more police making the city safer."

Former President Barack Obama introduced a $787 billion stimulus package after he won the presidency in 2008, including $2 billion in grant money to increase police forces. In Columbus, Ohio, where a $1.2 million grant provided money for only a year, the results were mixed. The department had to make cuts to its workforce anyway. Obama began his presidency at the height of the Great Recession, when the housing bubble burst, leading to a global financial crisis.

Calderón pushed back against Rougeot's narrative.

"Look up Vera Institute,” she said. “Look up Sentencing Project. Look up other studies that show — particularly for communities of color — more policing does not equal more safety."

She insisted that intervention programs — such as a social safety net, affordable housing, good jobs and unionized jobs — are the things that bring down the crime rate.

“So again, you don't know what you're talking about."

Rougeot did not have a chance to respond, and the debate went rolling along.

Trinidad Rodriguez defends "field hospitals," pushes back against notion of "internment camp"

Other candidates criticized Trinidad Rodriguez over his plan to house homeless people in a "field hospital" of sorts. Prior to the forum, former legislator Joe Salazar called the idea "an internment camp." Roy, one of the moderators, cited a tweet from RTD Director JoyAnn Ruscha, who called Rodriguez a "fascist."

Trinidad Rodriguez is a fascist who wants to round up poor and disabled Denverites and place them in prison camps.

— JoyAnn צדק צדק תרדף (@RuschaWrites) March 11, 2023

Sadly, he's not the only one. https://t.co/itJbqaXgyx

Rodriguez quipped back that state law allows it.

"Under Title 27 of the state's Colorado Revised Statutes, there is the power for governments and certain organizations to actually intervene when people are a danger to themselves and others," he said. "I respectfully disagree with those two individuals you mentioned. This is not an internment camp. It's a place where we can provide care for people who are suffering and dying today."

Title 27 of the Colorado Revised Statutes allows people to be imprisoned against their will, but it requires a court or jury decision.

"This is why people with a little bit of knowledge can be dangerous," Calderón said. "A mayor is not an emperor. You have to go through a legal process."

Rodriguez countered by citing his 25 years of experience working with homeless people. His plan, he said, is a balancing act of keeping people protected from drugs and homelessness, while also protecting their rights.

"It's a fantasy to talk about drugs not being a severe part of the problem, so I'm asking you — why won't you help somebody through a severe crisis like this?" he asked Calderòn.

"I've done that work, and that's not how the work gets done," Calderòn replied.

Al Gardner, an IT executive and Civil Service Commission member, said the country already tried internment, referencing the United States' internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. President Franklin Roosevelt's executive order was deemed unconstitutional in 1944 and repealed.

Rodriguez rejected claims that his plans call for an internment camp. He said he took "severe offense" to candidates likening those with a severe mental illness or health crisis to Japanese people. Later in the debate, he expressed interest in working with the national guard and U.S. military to explore how the organizations treat mental health issues.

"The U.S. military right now is innovating on mental health struggles among enlisted people," he said. "I believe we have an opportunity to build a best-in-class standard for how we actually care for people, keep everyone safe and get them into the kind of treatment they actually need."

When state Rep. Leslie Herod expressed concerns that Rodriguez wants to use the Colorado National Guard to "forcibly remove people" from Denver's streets, Rodriguez clarified he wants to work with the two organizations to develop care processes for people in his "field hospital" — not that he wants to deploy the National Guard or the U.S. Army to round up people, something he never, in fact, said.

Mike Johnston is at center of attention

The candidates peppered Mike Johnston with questions during a portion of the debate where they could directly pose a query to each other.

In particular, they pressed Johnston about three-figure contributions by wealthy California and Connecticut businessmen to an independent expenditure group supporting his campaign. Thomas Wolf, for example, asked a rhetorical question: Why are millionaires and billionaires "in this election" and why should they hold sway?

"I don't have people funding that entity who have interests before the city," Johnston replied. "So, I don't raise for it, I don't know who gives to it, but I think what I've seen is those are people who want to see politics that work."

Candidates have no control over these outside groups, which operate independently from campaigns. Colorado's laws expressly prohibit coordination with independent expenditure groups.

Wolf also alleged Michael Bloomberg made a contribution. SearchLight records — the city's campaign finance tracking system — shows this is incorrect. The last time Bloomberg engaged in a Denver campaign occurred in 2015, when he gave $150,000 to group campaigning on a ballot measure, the records show.

Sen. Chris Hansen wanted to know what Johnston's independent expenditure contributors will expect if he won the race.

"I think that's nothing because they've not had any conversation with me on what they do expect," Johnston said. "There's no expectation ... I think people are looking for leaders in a time when politics are broken."

At one point, Johnston raised more money than the entire field of candidates, drawing the most campaign contributions for the month of January.

Calderón and Terrance Roberts also grilled Johnston on his homelessness plan, which includes the construction of 1,400 "micro-communities" using $138 million in one-time federal stimulus funding for supportive housing. Roberts said he worries the conditions in the micro-communities or "Tuff Sheds," would not be sufficient for living. Johnston said they have heating and access to showers. He added the shelters would be "tiny homes," not Tuff Sheds.

Calderón said his plan doesn't address the short or long-term wishes of homeless people.

Johnston said his plan, indeed, addresses the city's long-term housing needs. The city can't build everyone a single family home which takes "three years and $500,000," he said, adding people don't have that kind of money and time.

"What we want is to begin building the capacity for long-term housing. That's why my plan has called for building 25,000 affordable units," Johnston said. "What we know is right now people need access to safe, stable protected housing and that does not mean living in a tent or encampment."