In his final public writing, beloved Denver journalist Dusty Saunders wrote of being orphaned at 9 years old and missing out on some of the basics of a normal childhood. He never became, for example, in any way tech-savvy. “I avoided those kinds of courses in school so I could play sports and chase girls,” he wrote last November. “Hey, there are worse vices.”

Saunders’ father died of a lung disease when he was 8. His mother died of a heart attack 18 months later. Dusty was their only child. But over the next 80 years, Saunders laid the foundations for two solid families: His blood family with wife Anita, and his loyal readership.

Though he never did master how to replace a ribbon, Saunders wrote, “I did eventually learn how to handle a typewriter pretty well, and I found a career that I loved.”

That career was writing … and writing … and writing … mostly about the local and national media as the broadcast critic for the Rocky Mountain News and, after its folding in 2009, The Denver Post. He is believed to have written more stories for The Rocky Mountain News than anyone in that paper’s long and storied history. And he did it with an accessible charm and almost miraculous absence of cruelty.

“They don’t make them like Dusty anymore,” journalist and former White House press Secretary Bill Moyers once said of Saunders. “He brought nobility to the greatest generation of ink-stained wretches ever to manhandle a remote control.”

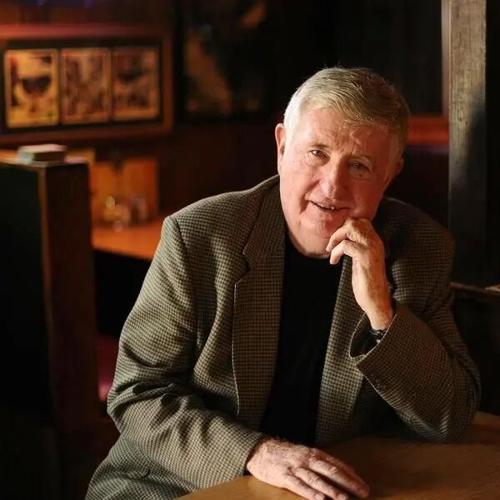

Saunders, who died Sunday at age 90, kept the media honest while somehow managing to never make an enemy.

He was, in his son Patrick’s words, “a giant of Colorado journalism.” He was among the last of Denver’s once large field of specialized writers before the ongoing wipeout of journalism jobs turned most all remaining reporters into generalists.

“I think his passing closes a chapter of journalism in Denver,” local freelance writer Dan Danbon wrote today. “He was THE media columnist in Denver. Moreover, he was a decent guy, always gregarious and friendly, with not a whiff of snobbery about him.”

Denver Mayor Michael Hancock said today that he grew up reading Saunders’ columns. “Dusty was one of a kind, a great writer who was always honest and clear,” Hancock said. “He represented the very best of times in journalism in Denver when facts mattered and he always articulated the thoughts of his readers. He was a community soldier indeed.”

A young Dusty Saunders.

Walter Patrick “Dusty” Saunders was born Sept. 24, 1931, in Denver. He grew into a skinny, 6-foot-3 star basketball center with a wicked hook shot for Holy Family High School in north Denver. “During his senior year, a Denver Post sports writer wrote that my dad was the best hooker in Denver's high schools,” Patrick wrote on the occasion of his father’s 90th birthday.

Though the Holy Family class of 1949 only numbered 96, Saunders counted among his classmates Jerry Kennedy, a larger-than-life Denver cop who also died this month. Saunders went on to play basketball at two Colorado junior colleges before graduating from the University of Colorado Boulder.

A clip from the 1949 Denver Catholic Register reporting on a Holy Family basketball playoff game.

Saunders started his journalism career In the fall of 1953 as a copy boy at the Rocky Mountain News, where he worked for 56 years. He covered the police and city-hall beats and was a harried and overworked editor of the paper’s features section before launching into his 40-year, award-winning run as a media columnist. And that was a beat, ironically in retrospect, that he had to fight for.

“He had to convince his editors that writing about the new TV medium was a good idea – and he became one of the most popular newspaper columnists in Denver history,” said Joanne Ostrow, who covered the same beat for The Denver Post from 1984-2016.

Saunders made for an uncommonly friendly rival, Ostrow said. Probably because he was such a genuinely happy guy. The two co-hosted a popular radio show on KHOW and had a regular lunch date. Saunders, she said, was a man with a million stories to tell.

“Dusty was a wonderfully welcoming presence when I joined the beat,” Ostrow said. “He was a great journalist in addition to being a genuinely nice guy and a proud family man.”

When the Rocky was shut down in 2009, Dusty later said, “I cried like a baby boy.” For the next three years, he wrote a weekly sports broadcasting column for The Denver Post, and in 2012 he published his autobiography, “Heeere's Dusty: Life in the TV & Newspaper World,” which received accolades from all over.

“No one has covered sports on television as thoroughly as Dusty Saunders,” the late, legendary Dick Enberg said upon the book’s release. “He understood the machinations of TV coverage as well as the talent that covered the games.”

Dusty Saunders with his family.

Saunders married Anita Murnan, also a Denver native and now his wife of 67 years, in November 1955. Together they had four children: Katie, Patrick, Steve and Bryan, and six grandchildren.

All four kids were influenced by their father’s career path. Patrick covers the Colorado Rockies for The Denver Post, Steve worked for 11 years at KMGH Channel 7, Katie is a costume and wardrobe designer for movies and TV, and Bryan works in video production.

That’s a far cry from Saunders’ childhood, growing up lonely and out of place. “In the 1940s, my dad's companions were the radio, books and sports,” Patrick wrote. “He became a St. Louis Cardinals fan because his radio could pick up the strong signal from KMOX Radio in St. Louis." For Dusty’s milestone 90th birthday, Patrick bought his dad a Cardinals T-Shirt with Stan Musial’s image and the words “The MAN.”

When Saunders’ mother died, Dusty was nearly sent to an orphanage. “My dad had brothers and a sister in Texas, who really didn't step forward,” he wrote. “And my mother had no siblings.”

Enter the woman he called “Auntie Sly,” even though she did not have a sly bone in her body.

Sylvia Easton had worked with Dusty’s mother at the telephone company. She and her husband, Dave, took Dusty in and raised him, along with their own daughter and son. But their relationship was not the stuff of loving TV sitcoms, Dusty said. Sylvia was aloof; Dusty was scared. But years later, when a grown Dusty started his own family, “I came to realize Auntie Sly saved my life,” he said. That’s when he found out that, without her, he would have been sent to an orphanage where he might have thrived anyway – but because Auntie Sly stepped up, he never had to find out.

Though there was no life insurance or inheritance, Sylvia paid to send Dusty to St. Catherine's and Holy Family Catholic schools in north Denver, in keeping with his mother’s wishes. She and Dave supported Saunders all through college. She died in 1990 at age 99.

Over his lifetime, Saunders’ love for Denver, and its institutions, were interchangeable.

In the early 1960s, the fledgling Denver Broncos gave away season tickets to the media and their families. When the team became popular and newspapers instituted ethics policies, local sports writers were given the option of keeping their season tickets for purchase. “We had those tickets in the family for nearly 50 years,” Patrick said.

When John Elway led "The Drive" in Cleveland that sent the Broncos to the 1987 Super Bowl, Dusty was on assignment in Southern California. “He watched the game alone in his hotel room,” Patrick wrote. When the Broncos won the game in historic fashion, “my dad got so excited that he picked up a startled housekeeper and gave her a bear hug when she entered the room.”

Saunders was a founder of the Television Critics Association, “which pushed the networks for access and made the whole endeavor of entertainment reporting more professional,” said Ostrow. Saunders is also a past president of the Denver Press Club, where he is a member of its Hall of Fame.

But he also loved music, counting among his favorites Gene Kelly and his umbrella sloshing through the streets in “Singing in the Rain”; tenor sax great Stan Getz performing “Moonlight in Vermont”; Frank Sinatra singing “New York New York”; and the Broadway showtunes “Somewhere” from “West Side Story” and “What I Did for Love” from “A Chorus Line.”

Saunders attempted to retire in 2012, when his book was published and his bones started to creak. “Mistake,” he wrote. “My normal sunny Irish disposition was too often replaced by that terrible condition – grumpiness." So in May 2019, he launched a blog, of all the tech-savvy electronic things, and he shared his Twain-like witticisms with readers through last November.

A memorial service will be held at 12:30 p.m. Thursday, June 16, at the Montview Boulevard Presbyterian Church, 1980 Dahlia St. Reception to follow from 3-5 p.m. at the Denver Press Club, 1330 Glenarm Place. In lieu of flowers, please consider a donation to Shalom Park in Saunders' name.

The 1949 Holy Family High starting five.